Harnessing Immobilized Enzyme Technologies for Advancements in Food Processing

[Name Redacted] Zahra XXXX, Mohammad XXXX, Tara XXXX, Aref XXXX, Reza XXXX, Saghi XXXX, Fatemeh XXXX, Zahra XXXX, Zoheir XXXX, Ali XXXX, Mohammad XXXX, Sharareh XXXX*, Gholamreza XXXX*

[Affiliations Redacted]

Correspondence to:[Redacted]

Received: November 22, 2025; Accepted: December 11, 2023; Published: December 19, 2023

Citation: [Name Redacted]. Harnessing Immobilized Enzyme Technologies for Advancements in Food Processing. J Nutr Food Sci. 2025;4(2).

Copyright: © 2025 Medprecis Research Group. This work is distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND license (Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives-No Modifications). Author information has been redacted due to compliance reasons.

Abstract

Enzymes have been at the core of food industries as they assist in flavor creation, modifying texture, and extending shelf-life. No matter how specific and efficient they are, their direct use in industrial settings is quite limited due to instability under harsh processing conditions and difficulties in recovery and re-use. To address these issues, immobilized enzyme technologies have proven to enhance enzyme efficiency and broaden their industrial use. This article examines the specific industrial uses and advantages of enzyme immobilization and its impact on food processing. Biological catalysts whose primary role is to enhance the speed of chemical reactions, are of no practical use because they are sensitive to practical environments. Coupling enzymes to solid supports enhances their stability and makes them easy to recover and use repeatedly. This review articulates diverse techniques of immobilization and focuses on novel techniques and developments in enzyme technologies, particularly the use of nanomaterials. Results of research on food production demonstrate that immobilized enzymes are extremely beneficial and cost-effective because they are easy to recover and can be used repeatedly. The only downside is that their primary usage is to immobilized enzyme due to the initial investment and the remaining activity being lost. Future research should focus on refining immobilization methods, sustainable strategies, and environmentally friendly practices to improve efficiency, scalability, and eco-compatibility across industries.

Keywords

Enzyme immobilization, biocatalysts, food industry, nanomaterials, enzyme stability, sustainability.

Introduction

Enzymes play a critical role in a wide range of industries due to their ability to act as catalysts, accelerating chemical reactions (Maghraby et al., 2023). These proteins are composed of amino acids and can be categorized based on the type of reactions they facilitate, such as oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolases, lyases, isomerases, and ligases. Additionally, enzymes are sourced from various origins, including animals, plants, and microorganisms, each contributing uniquely to their application in different industrial processes (Almeida et al., 2022).

Despite their effectiveness as biocatalysts in modern biotechnology, enzymes often face limitations due to their sensitivity to environmental conditions (Lyu et al., 2021). However, a notable advantage of enzymes is their remarkable ability to precisely control reactions, allowing for immediate halting when necessary. This characteristic makes them invaluable in various industrial processes where precise regulation is crucial. Additionally, they are capable of generating pure products without any impurities (Adhikari, 2019)

Over the past two decades, enzyme applications have surged across multiple industries, including dairy, baking, and beverage production like wine, beer, and fruit juices. However, the use of enzymes faces challenges due to their limited shelf life, lack of stability, and sensitivity to various processing conditions (Lyu et al., 2021, Maghraby et al., 2023). Derived from plant and animal cells, enzymes are natural catalysts highly valued for their compatibility with biological systems and biodegradability. They can accelerate chemical reactions even under tough conditions, yet they perform most effectively within specific ranges of temperature, pH, and other environmental factors. Deviating from these conditions can reduce their efficiency, often due to structural changes in the protein (Lyu et al., 2021).

Those methods that can rapidly synthesize nanocarriers under mild conditions allow for the one-step synthesis of nanocarriers and enzyme complexes, thereby exhibiting advantages such as simplicity of process, minimal enzyme damage, short processing times, and environmental friendliness (Hao et al., 2024). One effective approach to enhance the flow properties of packed bed reactors, including efficient mass transfer and high catalyst conversion rates, is the use of 3D printing. By creating optimized structures that prevent channeling and high-pressure drops, it is possible to achieve the desired outcomes (Eixenberger et al., 2023).

In the food sector, enzymes are increasingly popular as biocatalysts, yet they face challenges in maintaining activity, selectivity, and stability in harsh environments (Xie et al., 2022). Free enzymes can be compromised by extreme conditions, such as strong acids, bases, high temperatures, or organic solvents commonly used in industrial processes. These factors can lead to denaturation, resulting in the loss of their three-dimensional structure and, consequently, their catalytic activity. Additionally, the high cost of production, limited durability, and challenges associated with recovery and reuse present significant barriers to their widespread industrial adoption (Wu and Mu, 2022).

To meet the growing need for efficient biocatalysts, strategies like protein engineering, chemical alteration, and immobilization have been employed to enhance the performance and durability of enzymes (Lyu et al., 2021, Wu and Mu, 2022, Yushkova et al., 2019). Immobilized enzymes serve as catalysts that are easier to remove from reaction mixtures, making them highly desirable. In recent years, research has focused on using polymers to immobilize enzymes, aiming to improve their properties and expand their industrial applications.

Enzyme immobilization involves attaching enzymes to a solid support material, which prevents the enzyme from being dissolved or lost during the process while maintaining its catalytic function. This method enhances enzyme stability, making it more resistant to environmental changes such as temperature, pH, and solvents. Immobilization techniques are generally classified into three categories: physical methods (e.g., adsorption, entrapment), where enzymes are physically confined to the support; chemical methods (e.g., covalent bonding), where enzymes are chemically linked to the support via covalent bonds, providing greater stability; and hybrid methods, which combine both physical and chemical approaches to achieve superior enzyme activity and longevity. The key to successful enzyme immobilization lies in selecting suitable carriers and methods that preserve the enzyme's activity while improving its reusability and resistance to harsh conditions ( Tadesse & Liu, 2025).

Given that many enzymes dissolve in water, it can be difficult to retrieve and reuse them, leading to high costs. To overcome these issues, scientists have developed immobilization techniques that anchor enzymes to specific supports. This enhances their stability, facilitates their recovery, and allows for multiple uses, leading to significant cost reductions (Lyu et al., 2021).

For immobilized enzymes to be successful, they must maintain effectiveness and selectivity comparable to their free state. Additionally, they should be able to tolerate temperature fluctuations and pH variations and allow for easy retrieval and reuse. The support materials used for enzyme immobilization are generally categorized into inorganic and organic types. Among inorganic supports, silica (SiO₂) is widely used due to its stability and compatibility, which make enzymes more robust and simplify their recovery. Inorganic materials often exhibit better resistance to heat, pressure, and microbial attacks while being cost-effective.

Conversely, organic supports, particularly polymers, are valued for their adaptability, easy manufacturing, and modification capabilities, enabling ideal interactions with enzymes (Lyu et al., 2021). Various organic nanomaterials and polymers stabilize enzymes, increasing their robustness and allowing for repeated use. By securing enzymes to organic nanocarriers, their tolerance to heat, acidity, and storage conditions is significantly enhanced (Verma et al., 2020). It covers their preparation principles, post-immobilization performance, applications, and existing challenges (Hao et al., 2024).

Immobilizing enzymes using physical, chemical, or hybrid techniques addresses many challenges by increasing stability compared to free enzymes (Wu and Mu, 2022). An immobilized enzyme is fixed to an inert solid but retains its catalytic function (Xie et al., 2022). Interest in immobilized enzymes began in the 1960s, although the concept was first noted by Nelson and Griffin in 1916 when they observed that invertase could hydrolyze sucrose when bound to charcoal. Since then, numerous methods, both reversible and irreversible, have been created to improve enzyme properties for practical uses (Maghraby et al., 2023).

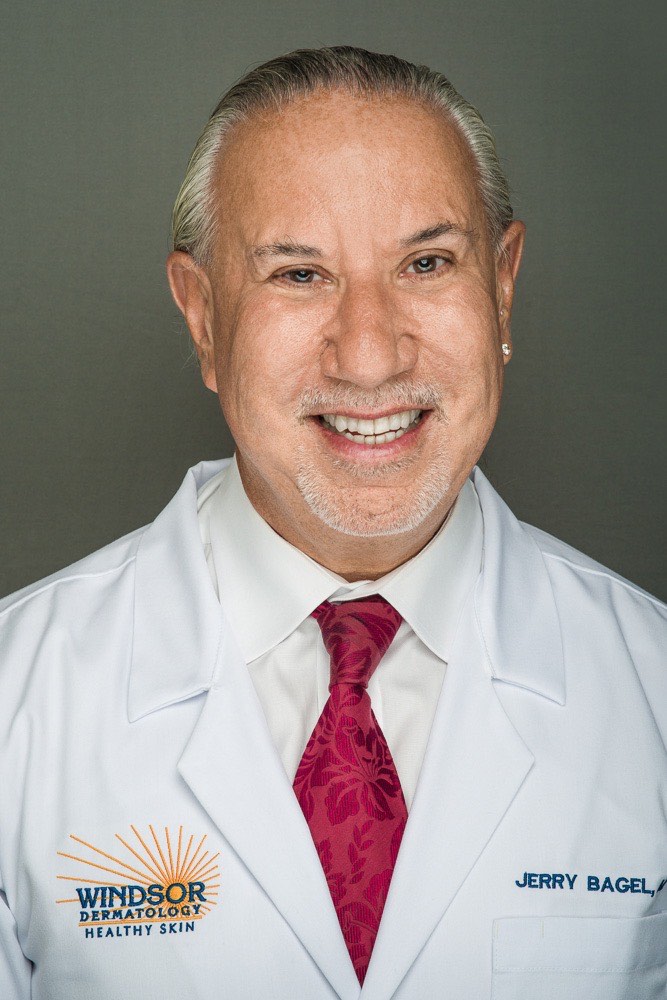

The goal of enzyme immobilization is to localize enzymes, making them more resilient to environmental changes, easier to reuse, and more economical (Almeida et al., 2022). Techniques for reversible immobilization include adsorption, metal interaction, and ionic binding, while irreversible methods encompass encapsulation and forming covalent bonds. Immobilization can alter enzyme properties, such as stability and recovery (Maghraby et al., 2023).

Whole-cell immobilization is an alternative that involves using entire cells containing desired enzymes instead of immobilizing individual enzymes. This approach confines viable cells within a defined space, allowing them to continue metabolic functions, thereby boosting overall performance (Khan, 2021b). The effectiveness, thermal tolerance, and pH stability of enzymes are influenced by the type of carrier, immobilization technique, and operational conditions. Suitable carriers for immobilization need to be non-toxic, biocompatible, and resistant to conditions encountered during reactions (Yushkova et al., 2019).

They should also have a strong affinity for proteins, relevant functional groups, and stability under heat (Yushkova et al., 2019). Hydrophobic carriers are often chosen when ionic strength is low, as substrate diffusion tends to be better on hydrophobic supports. For example, immobilizing lipase on a hydrophobic carrier often triggers interfacial activation (Enespa et al., 2023).

Recent advancements in enzyme immobilization within the food industry emphasize improving stability, cost-effectiveness, automation, efficiency, flexibility, and safety. These innovations have enabled new uses in bioprocessing, testing, quality control, and food packaging. The primary advantage of immobilized enzymes lies in their resilience to environmental changes and ease of retrieval for reuse (Xie et al., 2022).

In the 1950s, the first experiments to immobilize enzymes and enhance their properties were conducted, targeting enzymes like carboxypeptidase, diastase, pepsin, and ribonuclease using specialized resins. Later, researchers explored methods of coupling enzymes to carriers using diazotized agents (Khan, 2021b). Depending on how enzymes are anchored, immobilization methods are divided into physical (such as adsorption and entrapment), chemical (like covalent attachment), and hybrid techniques (like microencapsulation) (Xie et al., 2022).

The carrier material should be easy to modify, affordable, abundant, and eco-friendly. Advances in enzyme immobilization have produced stable and robust enzymes (Maghraby et al., 2023). Hybrid organic-inorganic nanomaterials have shown considerable promise in enhancing the properties of immobilized enzymes. These materials are expected to play a significant role due to their ability to improve the stability and activity of enzymes (Verma et al., 2020).

Nanomaterials offer unique properties, such as high surface area and mechanical strength, that make them ideal for enzyme immobilization. The latest innovations in enzyme immobilization include the use of silica, carbon, metals, and magnetic nanomaterials, which have shown promising results in enhancing enzyme stability and reusability. Notably, the integration of these materials into 3D printing technologies is opening new avenues for creating more durable and efficient enzyme systems (Rogacka and Labus, 2024).

The Specific goals of this research are to 1) Investigate various enzyme immobilization techniques and their impact on improving enzyme stability and reusability in industrial applications. 2) Address the challenges of enzyme instability under extreme environmental conditions, such as high temperatures, acidity, and organic solvents. 3) Develop more cost-effective immobilization methods that enhance the industrial viability of enzymes. 4) Examine the performance of immobilized enzymes in specific food production processes like starch processing, dairy, and brewing. 5) Evaluate the economic and environmental implications of using immobilized enzymes in these industries. This research aims to solve the issues related to enzyme reusability, stability, and performance under harsh processing conditions, offering practical solutions to the food industry. The expected outcomes include more efficient and cost-effective enzyme immobilization methods, leading to improved sustainability and industrial productivity.

This review stands out by combining traditional enzyme immobilization techniques with emerging innovations, particularly the use of nanomaterials to improve enzyme stability and efficiency. Unlike other reviews that focus mainly on methods like covalent bonding and adsorption, it also discusses the economic and environmental impacts of enzyme immobilization in food production, an often overlooked aspect. The review provides novel insights into optimizing enzyme reusability and scalability, offering a unique contribution to the field.

Figure1: Overview of enzyme immobilization methods. Reversible techniques include adsorption and ionic binding, while irreversible methods comprise covalent binding, entrapment, encapsulation, and cross-linking.

Immobilization Techniques

Enzyme immobilization encompasses a range of techniques, each offering unique strengths and weaknesses, as summarized in Table 1 (Maghraby et al., 2023). These methods can be broadly categorized into carrier-based and entrapment approaches (Bashir et al., 2020). The effectiveness of immobilization and the stability of the resulting enzyme depend on the chosen method and carrier material (Al‐Lolage et al., 2017).

A critical aspect of immobilization is maintaining the integrity of the active functional groups at the enzyme's active site, as these are crucial for proper enzymatic function. These groups must remain unaltered throughout the immobilization process to ensure activity is preserved (Khan, 2021a). Additionally, the enzyme's three-dimensional structure must remain intact, stabilized by weak interactions such as van der Waals forces, ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions. Any disruption to this structure during immobilization could lead to enzyme denaturation, significantly reducing its catalytic performance. To prevent this, the immobilization process must be conducted under carefully controlled environmental conditions (Khan, 2021a)

Covalent Binding

Covalent immobilization is highly regarded for its robust and stable bonds, which provide enhanced resistance to temperature, pH, and environmental fluctuations. For example, glucoamylase immobilized on κ-carrageenan exhibited an increased optimal operating temperature from 40°C to 60°C and retained full activity after 11 cycles. However, the Km value increased, indicating reduced substrate affinity, and the maximum reaction rate decreased from 2.28 to 1.11 μmol/min. While increasing bonding sites between the enzyme and carrier improves stability, it can reduce catalytic efficiency (Hassan et al., 2019).

Selective trimming of glucan binding sites and incorporating GST at the N-terminal followed by covalent binding to Eupergit C 250L achieved an 83.3% yield. Activation of the carrier is a critical step, with methods such as functionalizing silica with aldehyde groups proving effective in immobilizing lipase (Mohammadi et al., 2015). Novel approaches include immobilizing SpyCatcher within glyoxyl agarose gel for coupling with SpyTag enzymes (Tian et al., 2021).

In this method, enzymes are covalently attached to the surface of a carrier. For example, an enzyme like glucoamylase can be attached to a carrier surface through its active groups, such as hydroxyl or amino groups. Carriers typically include biopolymers like agarose, silica, or synthetic materials like Eupergit C 250L (Hassan et al., 2019). In this technique, the enzyme is initially activated using chemical groups, such as aldehyde or amine groups, on the carrier surface. The activation is typically done at a specific temperature range (e.g., 40-60°C) and pH (for example, pH 7.0) for a period of 2 to 4 hours. Statistical comparisons, such as ANOVA or t-tests, are commonly used to assess enzyme activity before and after immobilization (Tu et al., 2006).

Nanomaterials as Carriers for Enhanced Immobilization

Nanotechnology has revolutionized chemistry, medicine, and pharmaceuticals by enabling the advanced enzymes immobilization. Nanomaterials become ideal substrates for enzyme labeling because their high surface loading of enzymes can be accommodated at a smaller size, increasing efficiencies by increasing binding sites, improving diffusion, and allowing for customization of function (Ellis et al., 2021).

Bulky porous materials, nanomaterials minimize mass transfer by shortening the pore path, and provide higher chemical/thermal stability, biocompatibility, and kinetic efficiency (Liu et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025).

However, challenges remain, including complex synthesis challenges, coupled with environmental concerns arising from toxic production chemicals. A variety of nanostructures, such as particles, wires, tubes, sheets, and fibers, are used, including carbon-based materials (graphene, carbon nanotubes), metals (titanium, gold, magnetite), and oxides (silica and alumina). Recent advances have explored polymers, metal-organic frameworks, magnetic nanoparticles, and hybrid materials (Tadesse & Liu, 2025).

For example, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), which are composed of iron, nickel, aluminum, and cobalt, are widely used due to their magnetic reactivity. Magnetite (Fe3O4) is the most common magnetic nanoparticle for enzyme locking due to its low toxicity, high magnetic susceptibility, large surface area, biological compatibility, and superparamagnetic properties at ambient temperatures. Reports show that magnetic iron nanoparticles and Janus silica nanoparticles effectively immobilize protease and cellulase, and these immobilized enzymes have high stability under different temperatures and pHs (Herman et al., 2025; Tadesse & Liu, 2025) .

- SpyTag/SpyCatcher System

The SpyTag/SpyCatcher system is a modern biomolecular technology based on the specific interaction between a short peptide, SpyTag, and its protein partner, SpyCatcher. Upon binding, the two components spontaneously form a stable and irreversible covalent isopeptide bond. This property enables SpyTag-engineered proteins and enzymes to be efficiently and robustly attached to carriers or surfaces equipped with SpyCatcher. Due to its strength and versatility, this system has been widely applied in areas such as enzyme stabilization, vaccine design, industrial biotechnology, and biofuel production (Eswara & Fischle, 2022).

For ethanol production, stabilizing lignocellulose-degrading enzymes using dockerin-cohesin interactions and SpyCatcher/SpyTag systems has been effective under harsh conditions (Fierer et al., 2023).

Or, for example, one of the new approaches involves immobilizing SpyCatcher in a glyoxyl agarose gel for binding with SpyTag enzymes (Tian et al., 2021).

Adsorption

Adsorption relies on weak interactions like van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and ionic interactions. This method preserves the enzyme's structure and avoids altering the active site, making it less disruptive than covalent binding (Jesionowski et al., 2014). Successful adsorption requires matching the electric charges of the enzyme and carrier. For instance, cellulase immobilized on silica with a 3.8 nm pore size retained 63.3% activity at 50°C, demonstrating the importance of pore size and carrier surface area (Bayne et al., 2013, Chen et al., 2017).

Surface modification of carriers can enhance immobilization stability. Modifications such as methylation or functionalization with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane have been shown to improve lipase stability (Gao et al., 2009, Machado et al., 2019). Mesoporous Zr-MOF carriers used for immobilizing lactase resulted in improved durability and activity retention across multiple cycles (Pang et al., 2016).

In this method, enzymes are adsorbed onto the surface of a carrier through weak forces like van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding. For example, enzymes like cellulase or lipase may be adsorbed onto carriers such as silica or zirconium-based nanoparticles (Zr-MOFs). Adsorption generally occurs at ambient temperatures and near-neutral pH (around pH 7), with adsorption times typically lasting for 24 hours. To improve adsorption stability, the carrier surface may be modified using chemical groups like (3-amino-ethyl) triethoxysilane. Statistical tests, such as ANOVA, are used to compare enzyme activity levels at different stages of adsorption (Moerz and Huber, 2014).

Cross-Linking

Cross-linking, or carrier-free immobilization, involves directly bonding enzymes to each other, eliminating the need for a carrier. Techniques such as CLEAs, CLECs, CLELs, and CSDEs enhance specific activity and stability. For example, cross-linked lipase from Candida rugosa was stabilized using EDC-NHS and polyethyleneimine, resulting in improved thermal stability and enantioselectivity (Velasco-Lozano et al., 2014).

Applications of CLEAs span drug synthesis, food production, and cosmetics. For ethanol production, stabilizing lignocellulose-degrading enzymes using dockerin-cohesin interactions and SpyCatcher/SpyTag systems has been effective under harsh conditions (Fierer et al., 2023).

In this method, enzymes are cross-linked to each other through chemical cross-linking agents. For example, enzymes like lipase from Candida rugosa can be cross-linked using specific chemicals like EDC-NHS (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide). Cross-linking typically occurs at lower temperatures (e.g., 4°C) and may take anywhere from 2 to 4 hours depending on the enzyme and reaction conditions. Stabilizing agents like polyethyleneimine (PEI) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) may also be used. Results are generally compared using statistical methods like t-tests or ANOVA to evaluate enzyme activity before and after cross-linking under different conditions (Velasco-Lozano et al., 2014).

Entrapment

Entrapment immobilizes enzymes within solid or semi-solid matrices such as polyacrylamide gels, agarose, or silicone, allowing substrates and products to pass through while keeping the enzyme confined. This method preserves the enzyme's structure and catalytic efficiency (Bashir et al., 2020, Mohidem et al., 2023). A study using poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate stabilized α-glucosidase along with its co-factor, reducing enzyme leakage and enhancing stability (Demirci and Sahiner, 2021).

Approaches like photopolymerization and sol-gel techniques further enhance mechanical strength and stability. Agarose gels with 3% concentration demonstrated the highest efficiency for amylase immobilization (Chaudhary et al., 2019).

In this method, enzymes are entrapped within solid or semi-solid matrices, such as polyacrylamide gels or agarose. Common carriers include biocompatible materials like cellulose derivatives (e.g., poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)) or synthetic polymers like silica. Enzymes are typically entrapped in polymeric matrices through processes like photopolymerization or sol-gel methods. This method is particularly useful for enzymes that are sensitive to environmental conditions and need to maintain their three-dimensional structure. The reaction is usually carried out at ambient temperatures and at specific pH values that are suitable for the enzymes. Statistical methods, such as ANOVA, are used to assess enzyme stability and activity over time, comparing enzymes encapsulated under different conditions (Sassolas et al., 2013).

Encapsulation

Encapsulation involves enclosing enzymes within a chamber surrounded by a semi-permeable membrane, maintaining their soluble and active state. Materials such as κ-carrageenan, chitosan, liposomes, and nanoparticles are used, often requiring GRAS classification for food applications (Fang et al., 2011, Nedović et al., 2011, Singh et al., 2020).

For example, glucose isomerase encapsulated in alginate demonstrated excellent thermal stability (Singh et al., 2020). Combining encapsulation with other methods, such as cross-linking, can enhance mechanical stability, as seen in polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels used for penicillin G acylase (Wilson et al., 2004).

In this method, enzymes are encapsulated within semi-permeable capsules made from materials like alginate or chitosan. This technique is often used for enzymes like glucose isomerase or penicillin G acylase. Encapsulating materials may include alginate, liposomes, or nanoparticles. The encapsulation of enzymes typically involves processes such as droplet formation or gelation. These capsules are often stored at low temperatures (e.g., 4°C) and in controlled pH conditions. Statistical methods like ANOVA or t-tests are used to compare the enzyme activities of encapsulated enzymes under various conditions (Abd Rahim et al., 2013).

Table 1: The table shows a comparison of the results of different immobilization techniques on different enzymes.

Enzyme | Carrier | immobilization method | Result | Ref |

β-galactosidase | Calcium alginate | Encapsulation | High efficiency of lactose hydrolysis up to 72% | (Mörschbächer et al., 2016) |

β-galactosidase | Polyvinyl alcohol | Covalent bonding | High efficiency of lactose hydrolysis up to 75% | (Batsalova et al., 1987) |

Lysozyme | Sulfated chitosan that was grafted to a silicon wafer | Absorption | Most of bioactivity preserved | (Tan et al., 2014) |

Lysozyme | Chitin, chitosan | Covalent bonding | Longer half-life, 21 days | (Cappannella et al., 2016) |

Lysozyme | Cellulose | Encapsulation | Maintain enzyme activity | (Zhang et al., 2013) |

Transglutaminase | Magnetic nanoparticles | Covalent bonding | the enzyme was hyperactivated and showed 99% immobilization efficiency and 110% residual activity | (Gajšek et al., 2019) |

Glucose oxidase | COF nanosheets | Absorption | High selectivity and sensitivity toward glucose detection in electrochemical glucose biosensing | (Cao et al., 2024) |

Protease | Chitosan beads | Cross-linking | gluten content was decreased from 65 to 15 mg/kg In production of gluten-eliminated beer | (Benucci et al., 2020) |

Reversible Immobilization

Enzymes, as biomolecules, have a limited operational lifespan, losing catalytic efficiency with repeated use (De La Fuente et al., 2021). For large-scale industrial applications, recovering substrates after enzyme activity ceases is crucial to ensuring cost-effectiveness. Unlike irreversible immobilization methods that permanently bind enzymes to carriers, reversible techniques allow for enzyme detachment and reuse.

Adsorption, for example, offers nearly reversible binding due to its lower mechanical stability, while covalent immobilization, though robust and long-lasting, is typically irreversible. However, researchers are actively exploring options to create reversible covalent bonds (Bashir et al., 2020, Murata et al., 2018). A genetic engineering strategy involves tagging target proteins with a non-intrusive His-tag while modifying the carrier with nickel bonded to nitrilotriacetic acid. Nickel binds specifically to histidine groups, and this interaction can be disrupted by introducing imidazole or EDTA, which outcompete histidine, enabling enzyme detachment from the carrier (Liu et al., 2010).

A six-histidine residue tag is commonly applied, as the imidazole ring in histidine, with its electron-donating groups, forms strong yet reversible bonds with metal ions in the substrate (Bornhorst and Falke, 2000). In a study utilizing glyoxyl-octyl agarose, lipase immobilization demonstrated notable stability; however, the process remained irreversible. To achieve reversibility, researchers used octyl-glutamic (OCGLU) agarose. Treating octyl-agarose with glutamic acid formed an ionic bridge between the enzyme and the carrier, which could be disrupted using ionic detergents or guanidine, allowing enzyme recovery (Rueda et al., 2016).

Another experiment employed genetic engineering to attach calmodulin to the N-terminal end of enzymes such as organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) and lactamase. Two silica substrates and a cellulose membrane were modified with a phenothiazine ligand. This system formed bonds with calmodulin in the presence of calcium ions, but the connection could be broken with EGTA, which removes calcium (Daunert et al., 2007).

External triggers, such as temperature shifts, light exposure, or electromagnetic fields, can also facilitate enzyme detachment, with light being the preferred method due to its non-invasive nature. For instance, azobenzene (Azo) combined with cyclodextrin (CD) demonstrated reversible binding: trans-Azo fits snugly into CD, but upon UV light exposure, it switches to cis-Azo, disrupting the bond due to spatial hindrance (Wang et al., 2022).

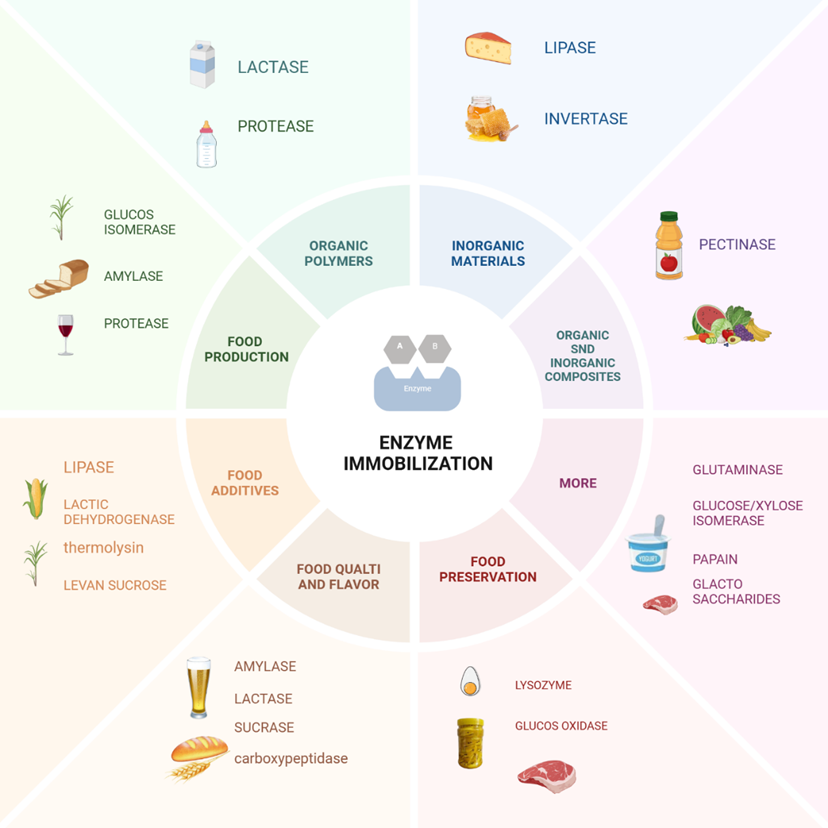

Figure 2: Enzyme immobilization applications in food processing industries.

Use of Disulfide Bonds

Disulfide bridges provide an effective method for reversible enzyme immobilization, allowing enzymes to be detached from carriers for support regeneration. Two main approaches are employed:

- Using materials that inherently contain disulfide bonds, such as cysteamine.

- Creating disulfide bridges through reactions between thiol-containing groups (Fraas and Franzreb, 2017).

In one study, a substrate with a carboxyl group bound to cysteamine in the presence of EDC/NHS. The epoxy-PEG linkage in this complex enabled the immobilization of various biomolecules. When the enzyme’s activity was depleted, the carrier was regenerated using 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) at 70°C (Fraas and Franzreb, 2017).

Laboratory techniques for creating disulfide bonds include genetic modification or chemical methods to introduce thiol groups to enzymes. Traditionally, 2-pyridyldisulfide-agarose (PyS2-gel) reacts with thiol groups on enzymes, forming disulfide links. These bonds are strong yet reversible and can be cleaved using dithiothreitol (DTT) (Batista-Viera et al., 2006).

Industrial Applications

Enzymes, as biological catalysts, play a critical role across various industries, including biofuels, food processing, pharmaceuticals, agriculture, leather production, paper, and textiles (Yadav et al., 2024). In the food industry, immobilizing enzymes on substrates has proven to be an effective strategy for managing production costs and streamlining manufacturing processes (Basso and Serban, 2019).

This sector encompasses diverse segments such as dairy, fruits and vegetables, grains, beer, meat and poultry, seafood, and packaged foods. Within these applications, enzymes are crucial for improving the nutritional value, taste, appearance, and texture of products. For instance, immobilized enzymes facilitate the continuous production of high-value ingredients such as high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), cocoa butter alternatives, allulose, and galacto-oligosaccharides, all of which are widely used in food manufacturing (Maghraby et al., 2023).

β-Galactosidase

The enzyme β-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23) is sourced from microorganisms, plants, and animals. It primarily hydrolyzes lactose, a sugar found in milk and whey, benefiting individuals who are lactose intolerant. By splitting lactose into simpler sugars, this enzyme enhances sweetness and solubility, enabling the production of diverse dairy products. In industrial settings, β-galactosidase is used for both continuous and batch processes, particularly when stabilized to maintain thermal stability and enzymatic activity. Recently, galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) have gained attention for their health benefits and use as prebiotics (Homaei et al., 2013). Producing GOS with β-galactosidase involves substrates of varying chain lengths (2–9 monomers), depending on the enzyme and reactor conditions, enabling the continuous conversion of lactose into GOS (Torres et al., 2010).

α-Amylase

Alpha-amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) hydrolyzes starch into smaller sugar units and is essential in large-scale food production. Immobilized alpha-amylases are preferred due to their enhanced stability and resilience under high temperatures. Unlike free enzymes, which lose catalytic activity under extreme pH, temperature, or pressure, immobilized alpha-amylases retain activity, resist inhibitors, and are reusable. Industrially, alpha-amylase is derived from fungal and bacterial sources, with species such as Bacillus, Thermomonospora, and Thermoactinomyces serving as ideal producers (Abedi et al., 2024, Mehrabi et al., 2024a).

Applications of Alpha-Amylase

- Sweeteners and Thickeners: Produces syrups containing glucose, maltose, and fructose for sweetening and thickening foods (Bahçeci, 2004).

- Bread Improvement: Converts starches into fermentable sugars for yeast, improving bread texture, flavor, and dough elasticity (Bahçeci, 2004).

- Fermentation and Alcohol Production: Breaks down starch into fermentable sugars used in beer and spirit production, playing a critical role in malting (Gomaa, 2018).

- Nutritional Enhancement in Cereals: Converts starch in cereals (e.g., wheat, rice, and corn) into digestible sugars, providing essential nutrients (McKevith, 2004).

D-Glucose/Xylose Isomerase

D-Glucose/xylose isomerase (EC 5.3.1.5) is vital for producing high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), the largest commercial application of immobilized enzymes by volume. Annually, over 500 tons of immobilized glucose/xylose isomerase are used to produce approximately 10 million tons of HFCS, a major sweetener in the food and beverage industry (Tufvesson et al., 2010).

Epimerase

Epimerase is widely used in the textile and food industries, particularly for converting fructose into allulose, a no-calorie sweetener with a sweetness profile similar to dextrose. Unlike traditional sugars, allulose is not metabolized by the human body, resulting in zero calories. Food manufacturers are increasingly using allulose as a substitute for sucrose to reduce caloric content. The production of allulose typically employs a continuous reactor operating with a fructose solution at pH 8 and 57°C, using coated columns with an 8 bed volume per hour flow rate for pumping and recirculation (Basso and Serban, 2019, Zhang et al., 2023).

Transglutaminase

Transglutaminase enzymes facilitate reactions such as cross-linking, acyl transfer, and deamidation. These reactions are critical in producing protein-based materials and thickeners used in foods like sausages, low-fat yogurt, and other protein-rich products (DeJong and Koppelman, 2002).

Lipase

Lipases (EC 3.1.1.3), sourced from bacteria, fungi, yeasts, and animal tissues, are versatile enzymes used in clarifying juices and wines, converting vegetable oils into margarine, and producing dairy products like cheese. Despite their potential, lipases are not widely commercialized due to high production costs and challenges such as sensitivity to pH and temperature. Immobilization methods have improved their stability, allowing for broader industrial applications, including enhancing bread production and other food processes (Coelho and Orlandelli, 2021, Thangaraj and Solomon, 2019).

Pectinase

Pectinase, primarily derived from filamentous fungi, is commonly produced through submerged fermentation. This enzyme is essential in juice and wine clarification but is typically used only once. To address this limitation, immobilized pectinase has been developed, offering increased stability at higher temperatures and acidic conditions compared to its free form. These advancements have enabled its reuse in food processing, enhancing cost-effectiveness and efficiency (Núñez-Serrano et al., 2024, Wang et al., 2023).

Table 2: Enzymes used in food industry along with carrier

Enzymes | EC | Enzyme substrate | Ref |

β-Galactosidase | (3.2.1.23) | Alginate gel, chitosan, PVA hydrogel capsules | (Anes and Fernandes, 2014, Hassan et al., 2024) |

α amylase | (3.2.1.1) | Polyethersulfone membrane, Chitosan | (Jalil and Asoodeh, 2024, Mehrabi et al., 2024b) |

D-glucose/xylose isomerase | (5.3.1.5) | Sepabeads EC-HA | (Neifar et al., 2020) |

Lipase | (3.1.1.3) | Graphene oxide | (Yao et al., 2022) |

3-epimerase | (5.1.3.31) | Graphene oxide | (Hong et al., 2014, Xiao et al., 2023) |

Pectinase | (3.2.1.15) | Magnetic nanoparticles, Polyethyleneimine cryogel | (Sojitra et al., 2016, Kharazmi et al., 2020) |

Advantages and Limitations of Enzyme Immobilization

Improved Stability and Reusability of Enzymes

One of the primary advantages of enzyme immobilization is enhanced stability under demanding industrial conditions, including temperature fluctuations, environmental changes, and extreme pH variations. This stability enables enzymes to remain effective even in non-water-based environments (Guzik et al., 2014).

For instance, in the food industry, cellulase enzymes are employed to remove undesirable colors from fruits and pulps. Stabilizing these enzymes addresses sensitivity issues during processing, extends their lifespan, and enhances efficiency (Maghraby et al., 2023). Similarly, immobilizing α-amylase on a BSF substrate increases its binding strength to starch and improves its stability. This method raises the activation energy needed for enzyme breakdown, making it more resilient than its free form (Abdel-Hameed et al., 2022).

Studies have shown that immobilizing α-amylase on a solid support increases its stability compared to free enzymes, with a 35% increase in thermal stability and improved pH resistance. The immobilized enzyme retained 95% activity after 10 cycles, while the free enzyme exhibited a significant decline in activity (Yandri et al., 2022).

Another significant benefit of immobilized enzymes is their ease of reuse. While recovering free enzymes from reaction mixtures can be challenging and expensive, immobilized enzymes can be easily separated and reused across multiple cycles. This feature is particularly valuable in industries like food production, where continuous processing is essential. For example, stabilized lactase used in producing lactose-free milk can be reused multiple times, reducing costs and promoting eco-friendly production practices (Bashir et al., 2020).

Enhanced Product Purity

The transition of immobilized enzymes from a soluble to an insoluble state facilitates their separation from the reaction medium, reducing the risk of contamination in the final product. This property is especially critical in food manufacturing, where product purity is paramount (Basso and Serban, 2019).

In a case study where glucose isomerase was immobilized on alginate, the purity of the final product was significantly improved, as the enzyme could be easily separated from the reaction mixture, leading to a 30% reduction in contaminants in the final syrup (Singh et al., 2020).

Economic Advantages

Immobilized enzymes offer numerous economic benefits:

- Cost savings through enzyme recovery and reuse.

- Increased efficiency in large-scale industrial applications.

- Production of enzymes with advanced and economically viable characteristics.

- The ability to immobilize multiple enzymes simultaneously (Maghraby et al., 2023).

Recent advancements in genetic engineering, optimized fermentation, and enzyme recovery techniques have significantly reduced enzyme production costs. Additionally, the reuse of stabilized enzymes lowers environmental impact by minimiz

Recent advancements in biotechnology and nanotechnology have enhanced enzyme immobilization strategies, leading to improvements in functionality and expanding industrial applications. The benefits include:

- Greater enzyme stability.

- Reusability.

- Improved efficiency and product purity.

- Adaptability to various production scales.

Ongoing research into carrier materials and immobilization methods aims to further optimize enzyme efficiency and increase product yields (Liu and Dong, 2020).

Controlled Catalytic Activity

Immobilization provides precise control over enzymatic reactions. By anchoring enzymes to solid supports, it is possible to optimize the arrangement and spacing of enzyme molecules, enhance reaction conditions, and increase overall efficiency.

This control is particularly significant in the food industry, where specific enzymatic processes are essential for achieving desired product qualities. For example, immobilized whey proteins are used in cheese-making to coagulate milk, a vital step in production. The use of stabilized enzymes enables controlled protease activity, minimizes undesired protein degradation, reduces contamination risks, and extends the shelf life of high-moisture cheeses (Zhang et al., 2015).

Reducing Inhibitory Effects

Immobilization can mitigate the inhibitory effects that arise during enzymatic reactions. In systems utilizing free enzymes, the accumulation of by-products or inhibitors can decrease enzyme activity and reduce efficiency. In contrast, immobilized enzymes are shielded by the immobilization matrix, which serves as a protective layer that limits access to the enzyme’s active site.

In a comparative study, the inhibition constant (Ki) of immobilized α-amylase was found to be higher than that of the free enzyme, indicating a reduced impact of inhibitors on the enzyme's activity. Immobilization on chitosan also enhanced resistance to product inhibition, with no significant decrease in activity observed after multiple cycles, while the free enzyme showed a reduction in activity under similar conditions (Ahmed et al., 2020, Tiarsa et al., 2022).

This feature is particularly advantageous in processes involving high concentrations of products or by-products (Maghraby et al., 2023). Immobilization often results in a higher inhibition constant (Ki) compared to the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km), reducing the impact of inhibitors on enzymatic reactions.

Solid carriers can further block inhibition zones associated with the enzyme, potentially eliminating inhibition altogether. While immobilization may sometimes decrease activity or modify catalytic properties, studies suggest it can also enhance enzyme function, leading to higher reaction rates per milligram of enzyme (Dik et al., 2023).

For example, covalently bonding amylase to chitosan increased thermal stability by 35%, improved resistance to pH changes, and boosted product yield by 1.5 times (Mehrabi et al., 2024a).

Challenges and Limitations

High Initial Costs

One of the significant challenges of enzyme immobilization is the high initial investment required. The costs stem from several factors, such as choosing the right substrates, designing the immobilization process, acquiring specialized equipment, and enzyme preparation and purification.

This financial burden can be especially problematic for smaller food producers or cases where cost savings from immobilized enzymes do not outweigh the upfront expenses. In industries with low production volumes or where immobilization does not significantly improve product quality, manufacturers may opt to use free enzymes, which, despite their disadvantages, are more affordable initially (Sheldon and van Pelt, 2013).

Potential Decrease in Enzyme Activity

Another major challenge of enzyme immobilization is the potential reduction in enzymatic activity. The process of attaching an enzyme to a solid support can alter its structure, leading to decreased catalytic efficiency. Several factors influence this activity loss, including the immobilization method, preservative properties, and fixation conditions.

Covalent bonding, a common immobilization technique, strengthens the enzyme-support material bond, improving stability. However, it may alter the enzyme’s active site, leading to reduced catalytic efficiency. Striking the right balance between stability and activity is essential when designing immobilized enzyme systems (Mohidem et al., 2023).

Structural changes during immobilization, shifts in the microenvironment caused by substrate interactions, and modifications in protein structure can also impact performance. Additionally, chemical agents used in the immobilization process may denature enzymes, reducing both reliability and consistency (Júnior et al., 2021).

Diffusion limitations present another issue. Immobilized enzymes can experience restricted movement of substrates and products toward and away from their active sites within the solid matrix, decreasing efficiency. Factors influencing diffusion constraints include matrix porosity, substrate size, enzyme concentration, and matrix thickness.

To mitigate these limitations, strategies such as using matrices with appropriate porosity, opting for thinner matrices, and employing stirring or liquid flow techniques are recommended. Properly managing these elements is crucial for optimizing bioreactor performance and ensuring efficient enzymatic reactions (Seenuvasan et al., 2020).

Difficulty in Choosing the Right Substrate

Choosing the right substrate for enzyme immobilization is crucial and often difficult. It must be compatible with the enzyme, create a stable environment without affecting enzyme activity, and remain stable under specific conditions. Additionally, it should be easy to recover and cost-effective. Balancing these criteria can be difficult and often requires compromises between different factors. This complexity makes substrate selection a significant hurdle in the immobilization process (Bashir et al., 2020, Zdarta et al., 2018).

Scaling Up for Industrial Applications

While enzyme immobilization techniques have demonstrated efficacy in laboratory settings, scaling them up to industrial applications poses unique challenges. Transitioning from small-scale to large-scale production introduces technical and economic hurdles.

Key concerns include:

- Achieving consistent enzyme distribution across the substrate.

- Maintaining stable enzymatic activity in larger quantities.

- Addressing mass transfer limitations, where substrate diffusion to the enzyme’s active sites is slower than the internal reaction rate, reducing catalytic efficiency.

Factors such as matrix porosity, hydrophilicity, enzyme loading levels, and operational variables (e.g., substrate concentration and temperature) significantly influence these limitations. These challenges can lower reaction rates, underutilize substrates, and ultimately reduce enzyme performance (Sigurdardóttir et al., 2018).

To address these challenges, strategies such as selecting suitable matrices, optimizing enzyme loading, and enhancing diffusion rates are necessary. For example, in large-scale glucose syrup production using immobilized amylases, ensuring uniform enzyme distribution in a large reactor is critical. Inconsistencies in enzyme distribution can affect product quality, which is a crucial consideration in food processing.

Moreover, the expenses and complexities associated with scaling up immobilization techniques may limit their adoption in the industry. It is essential to evaluate aspects such as profitability, scalability, stability, and catalytic performance when planning to use immobilized enzymes on an industrial scale (Choubane et al., 2015, Mohidem et al., 2023).

Table 3: Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Techniques: Covalent Bonding, Adsorption, CLEAs, and Entrapment in Food Industry Applications.

| Technique / Carrier | Stability | Cost | Reusability | Product Yield |

| Covalent Bonding | High stability (strong chemical bonds) | High cost (requires specific materials and advanced equipment) | High reusability (strong bonding to carrier) | High yield (effective enzyme activity) |

| Adsorption | Moderate stability (weak bonds to surface) | Low cost (simple method with fewer materials and equipment) | Limited reusability (weak bonds) | Moderate yield (reduced yield under specific conditions) |

| CLEAs (Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates) | High stability (cross-linked structure) | Medium cost (requires specific materials and equipment for CLEA production) | High reusability (good stability and resistance) | High yield (maintains enzyme activity) |

| Entrapment | Moderate stability (encapsulated in gel or polymer matrix) | Medium cost (materials for matrix and production) | Limited reusability (requires specific conditions) | Moderate yield (limited substrate access to enzyme) |

| Nanomaterials | Very high stability (nano-level properties) | High cost (requires advanced equipment and production of nanomaterials) | High reusability (stability and multi-use) | High yield (nanostructures increase enzyme activity) |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | High stability (organized and resistant structures) | Very high cost (advanced equipment for MOF production) | High reusability (pores and stability in diverse conditions) | High yield (active surfaces and high selectivity) |

| Sol-Gel Encapsulation | Moderate stability (silica gel coatings) | Medium cost (silica materials and production) | Moderate reusability (may have limitations) | Moderate yield (limited substrate interaction with enzyme) |

| Alginate-based Carriers | Moderate stability (depends on pH and temperature) | Low cost (affordable materials and simple production) | Limited reusability (may be unstable in some environments) | Moderate yield (may have limitations in volumes) |

| Chitosan-based Carriers | Moderate stability (depends on structure and environment) | Medium cost (requires specific processing for chitosan production) | Moderate reusability (reasonable stability under various conditions) | Moderate yield (limited substrate access to enzyme) |

| Polymeric Carriers | Good stability (matrix characteristics and improved structure) | Variable cost (depends on polymer type) | Limited reusability (depends on polymer type) | Moderate yield (limitations in substrate adsorption and transfer) |

Enzyme immobilization techniques offer various advantages and limitations, depending on the specific application. Covalent bonding provides high stability and reusability, ensuring high product yield due to the strong attachment of enzymes. However, it tends to be costly. Adsorption is a more cost-effective method, but it offers moderate stability and limited reusability, which can lead to lower product yield. CLEAs (cross-linked enzyme aggregates) offer high stability, reusability, and product yield, but they come with a moderate cost. Entrapment provides moderate stability and yield, but the confinement of enzymes limits reusability.

Nanomaterials are highly stable, reusable, and yield high results, although they are expensive. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) also offer high stability, yield, and good reusability but at a very high cost. Sol-gel encapsulation offers moderate stability and yield, with moderate reusability, though it may limit enzyme-substrate interaction. Alginate-based carriers are low-cost but have moderate stability and yield, along with limited reusability. Chitosan-based carriers provide moderate stability, yield, and reusability at a medium cost. Polymeric carriers, while offering good stability, are limited in terms of reusability and product yield due to enzyme-substrate interactions.

In summary, the choice of immobilization technique depends on the balance between cost, stability, reusability, and product yield specific to the industrial or research requirements.

Future Perspectives

Enzyme immobilization has become a cornerstone technology to overcome the limitations of free enzymes, especially in food processing. This technique enhances enzyme stability, reusability, and overall efficiency, making it an essential tool for industrial-scale applications. Various carriers—ranging from agricultural by-products to nanomaterials and metal-organic frameworks—have been developed to stabilize enzymes, enabling their use in demanding industrial environments. Immobilized enzymes are currently favored over free enzymes due to their longer lifespan and reusability, making them highly suitable for industrial applications (Datta et al., 2013).

Future research should focus on refining practical logistics and exploring innovative support technologies to enhance enzyme stabilization and expand their industrial utility. One promising approach involves leveraging metagenomic libraries and specialized databases to discover unique enzymes from non-cultivable sources, accelerating the development of tailored enzyme solutions (Ferrer et al., 2016).

Recent advancements in molecular biology have further contributed to creating stabilized enzymes with specific properties. Compared to their free counterparts, immobilized enzymes in the food industry offer improved catalytic efficiency, enhanced pH and thermal stability, and the potential for reuse, making them an attractive option for a wide range of applications. These include food manufacturing, quality control, agricultural contaminant removal, water treatment, and waste management (Hosseinipour et al., 2015).

Despite these benefits, challenges remain, such as ensuring long-term stability, minimizing environmental impact, and addressing recyclability issues. These challenges complicate the management and scalability of immobilization techniques.

Future research should focus on developing simpler, more effective immobilization methods that enhance sustainability and reusability. In addition to developing simpler and more effective immobilization methods, future research must address the regulatory and safety concerns related to novel materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and nanomaterials. Ensuring that these materials meet food safety standards and environmental regulations is crucial for their broader adoption in the food industry. Such advancements are essential for enabling continuous industrial processes and large-scale applications in the food industry. Addressing these challenges will ensure the broader adoption of immobilized enzymes, further enhancing their role in achieving industrial efficiency and sustainability goals (Taheri-Kafrani et al., 2021).

Potential Directions for Improving Enzyme Immobilization

Nanotechnology

Recent breakthroughs in nanotechnology have opened new avenues for enzyme immobilization, offering substantial improvements in enzyme stability and catalytic efficiency. Nanoparticles, due to their high surface area and tunable properties, provide a more efficient environment for enzyme stabilization, particularly in complex food processing systems. Nanoparticles, with their high surface area and improved catalytic activity, offer an optimal environment for immobilizing enzymes, enhancing their stability and performance (Hwang and Gu, 2013). Developments in nanoscience have introduced novel materials for enzyme stabilization, impacting fields such as biosensors, healthcare, food processing, and environmental remediation. Nanomaterials offer benefits such as biocompatibility, large surface areas, and customizable surfaces, which improve enzyme loading and stability (Wu and Mu, 2022).

Bioinformatics Advancements

Bioinformatics tools and advancements in enzyme engineering, such as directed evolution and rational design, have the potential to create enzymes with improved stability, enhanced substrate selectivity, and greater catalytic efficiency. Enzymes designed specifically for immobilization can exhibit superior stability and functionality, opening new possibilities for industrial applications (Sharma et al., 2021).

Multi-Enzyme Systems

Stabilizing multiple enzymes or developing reliable multi-enzyme systems is essential for optimizing complex industrial processes. Multi-enzyme systems, involving the co-immobilization of enzymes, are essential for efficiently catalyzing complex biochemical reactions. These systems allow for sequential or simultaneous reactions, significantly improving the overall efficiency and sustainability of food processing operations by reducing the need for multiple reaction stages (Schoffelen and van Hest, 2012).

3D Printing for Custom Immobilized Enzyme Complexes

3D printing technology provides opportunities to arrange enzymes with precision within stabilizing materials. This approach allows for the creation of customized and complex enzyme configurations, paving the way for innovative applications in bioprocessing, diagnostics, and product manufacturing (Shen et al., 2022).

Eco-Friendly and Renewable Carriers

Increasing attention is being given to eco-friendly immobilization techniques that utilize renewable carriers. Developing sustainable materials for enzyme immobilization is a growing research priority, aligning with global sustainability goals. These renewable carriers offer the dual benefits of reduced environmental impact and enhanced reusability of stabilized enzymes (Cavalcante et al., 2021).

Bioelectrochemical Systems

The integration of immobilized enzymes into bioelectrochemical systems is a promising field. These systems have potential applications in sustainable energy production, environmental protection, and healthcare. Current research focuses on understanding and enhancing interactions between enzymes and electrode surfaces to improve system efficiency and functionality (Mohidem et al., 2023).

Critical Assessment

This review has explored a wide range of enzyme immobilization techniques and carriers applied in the food industry, from traditional approaches such as covalent binding and adsorption to advanced strategies involving MOFs, nanomaterials, and co-immobilization systems. Despite the progress in developing various methods, several challenges and limitations persist, warranting a more nuanced evaluation of their practical implications.

From a cost-benefit perspective, while techniques like entrapment and CLEAs are often attractive for their simplicity and low toxicity, they may fall short in recyclability and long-term stability, especially in high-throughput industrial settings. On the other hand, methods such as covalent binding or advanced carriers like MOFs and nanomaterials provide high stability and reusability but introduce concerns regarding scalability, regulatory approval, and potential safety risks. This variation underscores the importance of tailoring immobilization approaches to specific food sectors, depending on factors such as target product yield, processing conditions, and consumer safety.

In particular, regulatory frameworks around the use of novel carriers—including nanomaterials and MOFs—remain underdeveloped in many countries. Their interaction with food matrices, potential toxicity, and environmental impact must be critically assessed in future studies to ensure compliance with food safety standards. Additionally, co-immobilization of multi-enzyme systems presents promising opportunities for process intensification and metabolic channeling, yet it requires deeper investigation in real-world food applications to evaluate its efficiency compared to single-enzyme systems.

To enhance future applications, interdisciplinary collaboration among food technologists, materials scientists, and regulatory bodies will be crucial. Research should focus not only on improving catalytic performance and cost-efficiency but also on addressing practical barriers such as carrier biodegradability, scalability, and consumer acceptance. Moreover, the development of standardized protocols for evaluating immobilized systems in food processes could bridge the gap between academic research and industrial practice.

Overall, while significant strides have been made in enzyme immobilization, a more integrated and application-driven research agenda is essential to fully unlock its potential in food biotechnology.

Future Applications of Inorganic Nanomaterials in Enzyme Immobilization for Food Processing

The use of stabilized enzymes in various sectors offers promising opportunities for improving efficiency and sustainability. Below are the critical trends expected to shape the future of enzyme immobilization:

Enzyme Use in Dairy Products: The demand for enzyme applications in dairy production is growing to enhance processing efficiency and produce nutritionally enriched products to address malnutrition and obesity. Stabilized enzymes, particularly lactase biosensors, are expected to drive innovations in this area.

Active Packaging Materials: The integration of stabilized enzymes into active packaging materials, such as antimicrobial films, oxygen absorbers, and moisture regulators, will play a crucial role in enhancing food safety and extending shelf life. Future research will focus on addressing high costs and storage limitations to facilitate broader commercialization.

National Security Applications: Stabilized enzymes are poised for use in protective equipment and environmental safety, such as air filters and water treatment for pesticide-contaminated water, contributing to public health and environmental risk mitigation.

Applications in the Food Industry: Immobilized enzymes like glucose oxidase will continue to be used to improve product stability, quality, and shelf life in food processing by reducing oxidative stress in beverages.

Safety of New Support Materials: The development of novel materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) will drive innovation in enzyme immobilization. Future research must focus on addressing safety concerns regarding toxicity, as well as exploring advanced technologies like 3D printing and coaxial electrospinning to expand the scope of enzyme applications.

This review has presented a comprehensive overview of ten key thematic areas related to enzyme immobilization in the food industry. The findings underscore that while numerous immobilization techniques such as covalent bonding, adsorption, CLEAs, and entrapment offer diverse advantages, their practical application in food systems is often dictated by a balance between performance, safety, and cost. Our analysis aligns with the primary objective of the review: to map out both established and emerging approaches, evaluate their industrial significance, and highlight novel materials (e.g., MOFs, nanomaterials) and configurations (e.g., co-immobilization) with high transformative potential. The consistency of our findings with current global trends in sustainable food processing validates the need for multifunctional, recyclable, and safe enzyme systems. This review contributes to the field by synthesizing scattered knowledge into an integrated framework, which can serve as a reference point for both academic researchers and industry stakeholders. Future efforts should focus on:

- Developing eco-friendly and food-grade immobilization carriers

- Advancing co-immobilization and multi-enzyme cascade systems

- Improving regulatory assessment methods for novel materials

- Promoting cost-benefit evaluations across different food sectors

By addressing these dimensions, the enzyme immobilization field can better meet the demands of modern food technologies and sustainability goals.

Conclusion

The study carried out on different enzymes and their carriers shows that the use of immobilized enzymes in the food industry brings stability, reusability and production yield. Enzyme immobilization technologies brings down the costs of production and enhances the stability of the enzymes. Among the carriers that are common in the market, MOFs and nanostructures mark the envelope in the next step towards progress of high-efficiency systems. Economies of scale are the major hurdles in widespread adoption. Research should on immobilization techniques that are integrated with environmentally sustainable practices. These in turn would complement the use of immobilized enzymes that would result in more efficient and cost-effective systems while supporting the environment.